Which Strategy is Right for My Company? Part 5- “Holy Futures, Batman!”

Previously, in “Generating Ideas,” we looked at ways to conjure up options for your company. By using the same techniques from your competitors’ perspectives, we could imagine what they might do. Their world looks different through their eyes than yours.

So you’ve got ideas for yourself and about them. There’s one more piece: context. A strategy designed for boom times can hemorrhage if times go bust. One designed for bust can lose ground to competitors if times go boom. Here, we’ll discuss context. In other words, scenarios.

39,382,200

I conducted a business war game for a well-known company. At the start I had each team — role-playing their business, their key competitors, customers, investors, suppliers, regulators — spend just 10 minutes listing the things they could do. The lists were not trivial variations such as “spend $10 million,” “spend $11 million,” and “spend $12 million.” They were qualitatively different actions.

The number of possible combinations was 39,382,200. No joke, no exaggeration, no misprint.[1] Holy futures, Batman.

Since the company had come up with about 10 strategy ideas for itself, that meant each of their strategy options could find itself in any of 3,938,220 possible futures.

Obviously, the large majority of those possibilities were highly improbable. Let’s heroically assume they could eliminate, quickly and without error, the 99.99% least-likely scenarios. That would leave 394, which is 391 more than the best-case, worst-case, most-likely-case analysis that companies typically perform. (An analysis that heroically assumes they can spot the best, worst, and most-likely cases in the first place.)

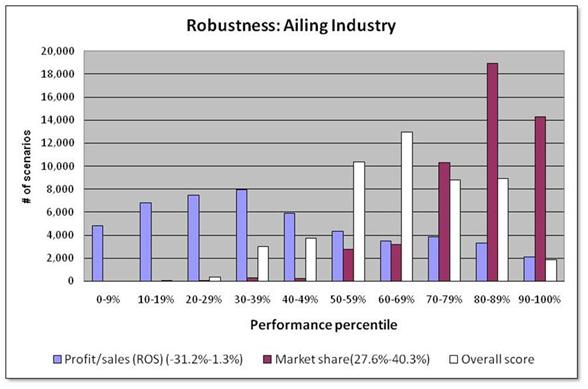

Now, it is possible to analyze large numbers of scenarios. Monte Carlo simulation works for certain classes of scenario problems. My own strategy decision test technology can look at about a million scenarios per minute and produce fabulous charts like this.

(That chart shows a particular strategy is likely to do well on market share whereas its performance on profitability could be almost anything.)

But that’s not the core issue at hand.

For many companies, especially smaller ones, the core issue is less about calculating and more about imagining. Here are the key ideas:

- It is not possible to know the future.

- It is possible to describe and explore possible futures.

- Exploring possible futures helps you make better choices and thereby raise the odds that you’ll do well.

What you want to look for are futures that 1) are likely, 2) would make a difference in your performance, and 3) for which you are unprepared.

Think about an asteroid heading our way that neither Bruce Willis nor Clint Eastwood can deflect. You’re probably not prepared for it and it would make a big difference in your performance, but it’s not likely. Plus, if an asteroid strikes, you and I have got problems bigger than quarterly sales quotas. Unless you’re in the asteroid-deflection business, that’s a scenario you can ignore.

A supply-chain disruption is more likely than an asteroid strike, and it could affect your performance. Notice the fairly broad scenario: supply-chain disruption. In a sense it doesn’t matter whether a tsunami floods a factory, a ship is hijacked, truckers go on strike, a hurricane cripples a port, an earthquake or tornado rips apart key roads, political instability cuts off a raw material, etc. (Gee, this is depressing.) Any one of those specific events is improbable, but the odds of something disrupting your supply chain is, well, less improbable.

Having scoped out the myriad ways your supply chain could be strained or snapped, you might consider action. For example: buffer inventories, second or third sources of supply, hedging or insurance, switching to more-easily obtainable components or ingredients, etc. You might choose to make tradeoffs between certainty of supply and lowest-possible cost.

The point is not that you could change your supply chain. The point is that exploring the futures that affect your business can help you make wise strategy decisions.

The process for generating strategy ideas (in the previous essay) can be a good source of ideas for important scenarios. When you ask questions such as “what has to happen for our strategy to succeed” or “what could happen that would cause our strategy to fail,” you’re automatically giving yourself a head start on nominating important scenarios. Go to those lists and ask how likely they are, how much different they’d make, and how unprepared you are.

View Part 1 of the Series – What You Want

View Part 2 of the Series – What They Want

View Part 3 of the Series- Speaking the Same Language

View Part 4 of the Series- Generating Ideas

Coming up next

We’ve talked about defining success, generating strategy ideas, and imagining the scenarios in which we will act. We’re ready to start talking about choosing a strategy.

About the author

Mark Chussil is Founder and CEO of Advanced Competitive Strategies, Inc. and a 35-year veteran in competitive strategy. He has designed strategy simulators and conducted business war games for dozens of companies, in many industries, around the world, helping them make or save billions of dollars.

A highly rated and entertaining speaker, Mark speaks about strategic thinking at conferences and in corporate workshops. He has written three books, chapters for five others, and numerous articles, and he has been quoted in Fast Company, Harvard Management Update, The Wall Street Journal, and other publications.

Mark is also a Founder of Benefitics, LLC (which quantifies Social ROI for non-profit organizations) and a Founder of Crisis Simulations International, LLC. He earned his B.A. at Yale and his M.B.A. at Harvard.

Featured Image Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/ssm316/4492194135/

Category : Business Growth & Strategy

Tags: Strategy